By Ray Cavanaugh

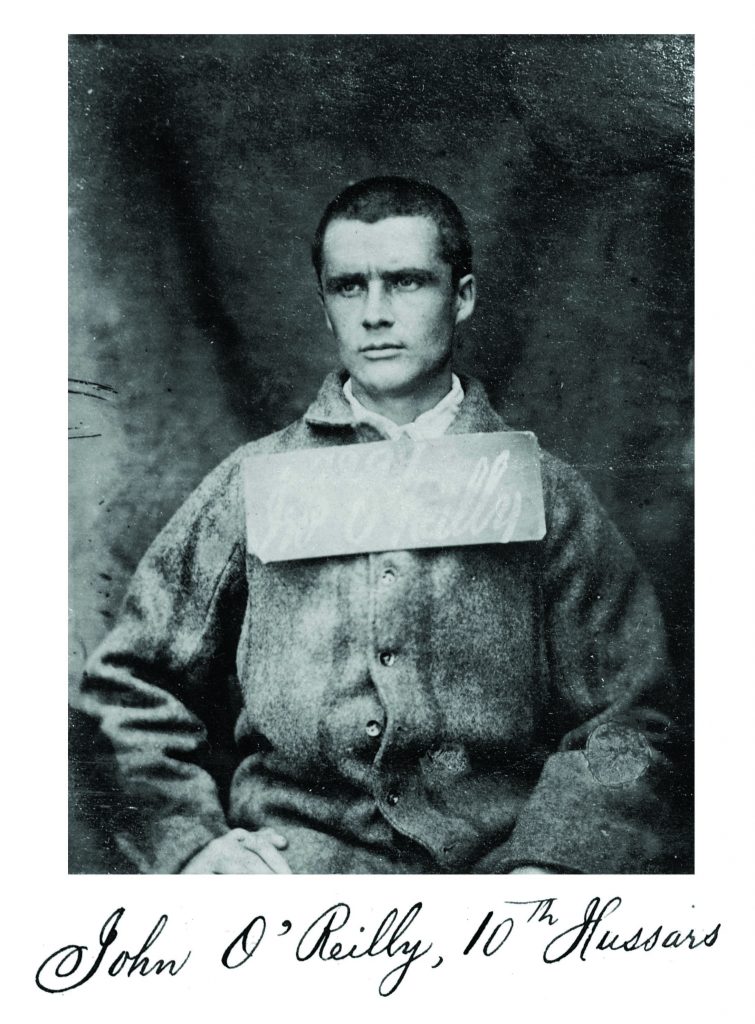

Born in County Meath, Ireland, in 1844, John Boyle O’Reilly joined the British army as a young man. This would’ve been fine with Her Majesty, except that O’Reilly also joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

For his involvement in this political subversion, he was sentenced to 20 years of penal servitude in Western Australia. After languishing in British prisons for two years, he was put on board the Hougoumont – the last British ship used to transport convicts to Australia.

Following a three-month voyage, the ship docked at Fremantle on 9 January 1868. O’Reilly was brought to Fremantle Prison, where he was appointed as a librarian to the prison’s Catholic chaplain, a Father Thomas Lynch.

William Schofield’s biography Seek for a Hero narrates the scene of Fr Lynch, himself an Irish native, offering O’Reilly a cigar and then asking him, “What do you plan as a prisoner here in Australia”. The convict replied, “Father, I’ve only one plan: Freedom”.

O’Reilly spent only a few weeks at Fremantle before he was transferred to Bunbury to build roads alongside other convicts, many of them hardened criminals who had been cast away from British penitentiaries.

There was something different about the learned O’Reilly, who had acquired a reputation for establishing a handwritten newspaper while on board his prison ship to Australia. He was soon relieved of his back-breaking labour so he could perform account keeping and other administrative duties for his warder, Henry Woodman.

As part of his job, he frequently delivered letters to the warder’s own residence, where he formed a relationship with the warder’s daughter, Jessie Woodman. It ended badly. The reasons are unclear, and it doesn’t appear that the warder (assuming he knew) took any action against him.

In fact, it appears that inmate O’Reilly’s real punishment was a broken heart. He wrote angst-ridden poetry and then, on 27 December 1868, attempted suicide. Another inmate discovered him unconscious and bleeding from the slashed veins in his left arm.

His life was saved, but clearly it was time for a change of venue. While in Bunbury, O’Reilly had befriended another priest, Fr Patrick McCabe, in whom he also confided about his ambition to escape.

Fr McCabe considered it a “wild dream” and told him, “Better forget it – right away”. But O’Reilly persisted, and so the priest began to plan with him.

On 18 February 1869, messenger O’Reilly was running a bit late. And there was a very good reason. He had joined a group of Irish friends, rushed to the Collie River, boarded a well-concealed rowboat, and paddled into the Indian Ocean.

Having covered some 20 kilometers, the rowboat docked at the Leschenault Inlet, where O’Reilly and his cohorts hid in the sand dunes. Old friend Fr McCabe had surreptitiously contracted the Vigilant, an American whaler, to swing by and pick up O’Reilly and the others.

Catching sight of the Vigilant, the Irishmen jumped from their dunes and joyfully paddled towards the ship. However, the Vigilant Captain apparently had a change of heart, for his ship completely ignored the incoming paddlers and sailed away beyond the horizon.

O’Reilly & Co went back to hide in the dunes. Fr McCabe, learning of the Vigilant’s double-cross, arranged for an American whaler named the Gazelle to complete the original plan, which it did.

The Gazelle was initially bound for Indonesia, but, owing to tumultuous weather, headed to the island of Mauritius instead. At that time, Mauritius was a British colony, and when the Gazelle arrived, British authorities came on board, announcing that they were searching for fugitives. The ship Captain denied knowing anything about O’Reilly, but, to placate British authorities, surrendered a different, less-likable fugitive.

In the wake of this close call, the Gazelle’s Captain transferred O’Reilly to another ship, the Sapphire. When the Sapphire arrived in Liverpool some 10 weeks later, the fugitive was whisked away to another ship, the Bombay, which was bound for America, O’Reilly’s desired destination.

The Bombay docked in Philadelphia on 23 November 1869, more than nine months after O’Reilly’s escape. He soon relocated to Boston, where he began working for The Pilot, a staunch Catholic newspaper which strongly resonated with Boston’s ever-growing Hibernian contingent.

The Pilot grew into one of America’s most widely-circulated papers, and O’Reilly became its standout voice, holding the position as Editor and part-owner. For 20 years, he wrote editorials. In addition to guarding the interests of Irish-Catholics and fighting religious intolerance, he also championed the rights of workers and African-Americans, who, in spite of their recent emancipation from slavery, were still much-oppressed.

Along with these editorial endeavors, he produced three volumes of verse, a novel, and some of the country’s earliest fitness literature. His poetry enjoyed immense popularity and often was recited at public occasions. Though future criticism would dismiss many of these poems as crowd-pleasing verse, such poetical efforts as his “Cry of the Dreamer” have retained a more favourable critical standing.

In 1872, O’Reilly married a journalist, Mary Murphy, with whom he would have four daughters. Both literally and figuratively, he had journeyed far from his days of penal servitude. However, he was bothered by the idea that some of his rebel Irish compatriots remained as convict-servants in Western Australia.

So he lent his firsthand fugitive knowledge to a surreptitious endeavour involving a fake whaling ship, the Catalpa, which sailed all the way from New England to Bunbury to pick up six Irish escapees in a wild, elaborate 1876 mission known as the Catalpa rescue.

The Catalpa rescue was a success, and O’Reilly’s journalistic career was a triumph – for him and for his people. Yet all was not well, as he was battling a number of health issues, along with chronic insomnia. According to his friend and colleague, James Jeffrey Roche, O’Reilly had grown “perceptibly older” during the year 1889. He also became more reclusive.

During yet another sleepless night in 1890, he indulged in his wife’s sleep medicine. He was found dead the following morning on 10 August 1890, at the age of 46.

The epilogue of Ian Kenneally’s biography “From the Earth, A Cry” addresses the question of whether or not O’Reilly committed suicide. He’d tried it once before, though under much different circumstances. At that time, he had a shattered romance and nearly two decades of penal servitude on his plate.

O’Reilly had far more to live for at the time of his death. Kenneally points out that, “There is nothing in his writings prior to his death that suggests suicidal thoughts”. Though O’Reilly’s chronic insomnia might’ve been a symptom of depression, it also could’ve been caused by work-related stress, which is his biographer’s conclusion. Additionally, the sleep medicine in question, chloral hydrate, was a risky item that had led to a number of accidental deaths.

No autopsy was performed, and O’Reilly’s cause of death was reported as a heart attack. His body was placed in a temporary vault, as an appropriately grand memorial was undertaken at a nearby cemetery.

The City of Boston held a public commemoration in his honour, as letters of condolence from Ireland and the United States continued to flood the offices of The Pilot.